First, I want to thank my genius son, Sam, for this website. He tried to talk me into a website four or five years ago, and reserved the address for me. Thanks, I said then, but I already communicate with the public as much as I want to. Things are different this week, and I’m grateful Sam had the foresight to look out for old Dad.

I’ll be posting here at least weekly, for as long as you want, and perhaps longer.

I’ll open Blog One with some probably ineffective rumor control. Word in the ether is that I am (a.) expecting employment with the daily paper, (b.) writing scathing blogs under a pseudonym, or (c.) deathly ill, or perhaps dead already. None of these are true.

Of course, my denying them will convince some that all three are true.

I have no secret identities, except the ones I sometimes used at Metro Pulse over the years, that is, drama critic George Logan and Edwardian historian Z. Heraclitus Knox. I think there was some other fellow, too; I don’t recall for certain. But I don’t own a cell phone or a Facebook account, and I have never tweeted or texted or twerked in my life, although if you have a photograph of me doing one of those things late at night at Preservation Pub in some prior decade, I may not be in a position to argue. I’m not opposed to any of the electronic practices of our times, but have not prioritized them in my personal budget.

The first blogs I ever wrote, 15 years ago on the website K2K, were publicly critiqued in Knox County Commission, as evidence that journalists were, as imperfect human beings, biased, and perhaps that experience left me jumpy about it. The only blogging I’ve done since then has been via my seldom-seen Metro Pulse blog, the frequency of which was always limited by my ability to find my crib notes about how to blog. I’m terrible at remembering procedural sequences, whether it concerns blogging or starting a chain saw. And then there’s the matter of my most recent password, which I often had a hard time finding even when it was taped to my wall.

My ignorance of modern marvels owes something to the fact that it’s been some years since I’ve had a motive to find something to occupy my time. For the entirety of this century, Metro Pulse and books and talks and other freelance responsibilities have consumed nearly all my waking hours. I’d work a regular working week downtown, lucky when I could catch the 5:50 bus. Then every Saturday found me in the McClung Collection, often researching a Secret History that I decided was timelier than the one I’d just completed. Then every Sunday I was writing clues for the Metro Pulse crossword puzzle Ian Blackburn had prepared.

The only times I could keep Metro Pulse down to a 40-hour week were the weeks I was on vacation. Working on vacation was always my choice. I had such a backlog of stories, too many to tell in one lifetime, that I felt I couldn’t waste a single issue, and I didn’t want to annoy readers with a lame “Jack is on vacation” note.

No one was telling us to work that hard. I wouldn’t have done it just for a salary. We did it because we made Metro Pulse what it is, or was, without anyone telling us what to do, and we were proud of it and thought it made a real difference in our city.

Of course, after the long week was done, I had other things to do. Evenings are when I work on books and talks. In the last six weeks alone, I’ve given talks to roomsful of strangers on the subjects of art photography, local jurisprudence through the centuries, indie cinema, notable financial panics, architecture, and the future of journalism. I don’t know much about any of these things, but I learn enough about them to give a satisfying talk. An unexpected perk of this job is a liberal continuing education, but you do have to work at it.

I work on all sorts of random projects, mostly sitting at the computer. When I need to take a break, I’m inclined to get the hell away from keyboards and screens of all sorts. That’s when I like to cook, something simple like catfish, and to sit on the back porch and listen to jazz and sometimes read something by Graham Greene. You may like to do something else, but that works for me.

That, along with my Presbyterian instinct for thrift, and my horror at the prospect of carrying on my person anything that’s more valuable than I am, when at any moment I might get rained on or run over, is why I don’t carry a cell phone, and why I’m not intimate with the allegedly social media.

It’s not that I’m hiding, as some suspect, or that I disapprove of what all the rest of you all are up to. We live in interesting times, and I’m watching with interest.

But lacking other handy options, I’m going to give blogging another try, to see how it goes. This is my official notice.

My next blog will be shorter.

—

My main request is that you don’t worry about me personally. In the last four days I’ve seen people flinch when they see me, and give me the limp handshake I’ve felt only at family funerals. The other reaction, which is an improvement, is to buy me a beer. I appreciate all that, but it’s my own shortcoming that I just can’t get drunk as much as you all want me to. Maybe next month.

See, I’ve been working on two book projects for a year or more, and am behind on both. I have some more work after that. Without Metro Pulse, I may finally have this local-history thing down to manageable 40-hour week. Maybe I’ll finally even get to that damn novel.

Of course, these projects don’t come with health or retirement plans, and that’s something to worry about. And I have a stubborn tendency to put much more work into books and other projects than I meant to. I’ve never made minimum wage on a book. But they’re fun to make. I’ve done real work, and writing a book is not really like real work.

—

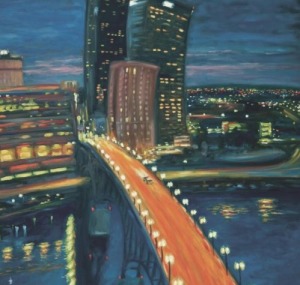

I will miss the weekliness of Metro Pulse, I’ll miss my talented colleagues, I’ll miss the immediate responses from smart readers. We had regular followers in Hong Kong, Cape Cod, Chicago, Nottingham, New Orleans, London, Morristown. I probably spent two hours a day just responding to them. I will miss having a bathroom downtown, and a phone, and a computer, and a chair and a window just above the marquee of a grand old theater, overlooking one of the busiest streets in the region. I’ll miss having a place where I can sit in the dark and look out and wonder what all those crowds are scurrying to see or hear.

I knew that part couldn’t last, and I knew it the day we moved in, more than eight years ago. The second floor of the Burwell never looked like an office for a scrappy free weekly. It’s an office suitable for a law firm, or a foundation, or, as it had been for a century before we moved in, a prominent insurance company.

For the record, the men’s room at the Burwell was exactly what you would expect of the men’s room for a free weekly. But the rest of the office looked like it should be occupied by people making three or four times our salaries.

An alternative weekly should be located in an old warehouse, or even an old parking garage or burnt-out factory, perhaps a superfund site, a place with exposed wiring and rats and a problem with break-ins, a place its owners had once intended to tear down. For a journalist, luxury is embarrassing.

—

I’ll miss my colleagues. All of them, including the freelancers I worked with, but I want to mention a couple I worked most directly with for many years and who didn’t get their names listed as prominently as often as those of us who were mostly writers did. Matthew Everett, who first began working for us first in the ’90s, before several years of adventures elsewhere, handled a hell of a lot of work with the music section and the calendar, especially as our staff was reduced, and legal concerns ended our longstanding intern program. Keeping up with all the moving parts of an entertainment section requires skills I lack. I know, because 30 years ago this month, I was named entertainment editor of a glossy monthly called Citytimes. It endured my leadership for about six weeks.

And Coury Turczyn, whom I actually met at Whittle Communications right about 27 years ago, when we were both low-level editors for ostensibly national magazines. Coury’s the main guy who got me involved with Metro Pulse so long ago, and he’s the best editor I’ve ever worked with, in terms of finding syntactical, organizational, and logical problems with my work, but also in finding writers I didn’t know existed. He was also a champion in getting us out at a reasonable time on deadline day. There was a time, in the last decade, when it was not unusual for several of us to still be working there at 10 or 11:00 at night. Under Coury’s watch, we were almost all done by 6:00. Every week, he absorbed the stress of all our little crises.

It’s remarkable that in the final weeks there were just 11 of us, including the sales staff. There were once more than twice that many. For the last several years, we’ve been working our asses off. None of us would have done that just for money. We did it because we were proud of what we had put together, and because we thought it was important, and because it was fun.

Metro Pulse has witnessed some major changes to the city of Knoxville, since 1991, and though we’re not investors or architects or elected officials, we’ve repeatedly found ourselves in the middle of things. Remember Knoxville in 1991? If you don’t, you have lots of company.

We were flogging Market Square back when it was empty at night and all weekend, and people thought of it as TVA’s personal lunchtime food court. We hailed the idea of a downtown movie theater when cinema professionals were assuring us they knew about these things, and it was simply impossible. We’ve repeatedly raised the idea, flabbergasting to many of our elders, that old buildings have value. We’ve seen the rebirth of real festivals in Knoxville; in the early ’90s, festivals were sad, lonely things, and erstwhile festival organizers informed us that Knoxville was inherently unfestive. We also heard that Knoxvillians would never choose to live downtown. Lately we’ve been looking around town, for other interesting streets and neighborhoods beyond downtown, and found quite a few of them. I don’t know, but I have the impression that we’ve played a role just in getting people interested in this old town again.

If I’m not sobbing and gnashing my teeth, it’s partly because I never really got used to the idea that human beings could make a living this way. It just doesn’t seem natural. Work is supposed to be unpleasant. Isn’t that why workers get paid, to compensate for it? Isn’t that why they are so eager for time off? I never wanted time off from Metro Pulse. It was interesting almost every day–and then we got recognition for it, and the gratification of causing a stir. People called and wrote every day, because they cared about what we were writing about as much as we did. It almost didn’t seem fair to the rest of humanity that even after all that we should also get a salary, even if it wasn’t a salary that would impress most freshly betasseled owners of bachelors degrees. It was a living, and I feel lucky that it was. I’m not sure what else people would have paid me to do for the last 19 years.

Also moderating my reaction is the fact that this isn’t the first, or second, time I’ve been laid off from a periodical publication. Thirty years ago this fall, I was arts and entertainment editor for a glossy monthly called CityTimes, a magazine based in a hole in the wall on Central Street. I’m not sure, but I think it may be a step great-uncle to CityView. The word “City” as a prefix was in the air in the ’80s, kind of like the word “Metro” was in the ’90s. In my youth, “City” was not the first word that came to mind when we thought of Knoxville. But somehow CityTimes seemed to be growing in stature and circulation until, suddenly that fall—I think it was just after Halloween—our primary investor, who was also invested much more heavily in the coal industry, got some bad news about a mine in West Virginia, and quit us, leaving us squirming and trying to find borrowed space for a magazine that was seeming more and more unlikely.

When it ended, my wife and I were expecting a baby, and the same month we were evicted from our apartment in Fort Sanders for a secret dog. (As it turns out, a Labrador Retriever is difficult to hide.) Then my Volkswagen was totaled when I was rear-ended by an uninsured teenager. Then, perhaps unsurprisingly, I was hospitalized for a heart-rhythm disorder. Just monitoring it and getting the welcome opinion that it wasn’t going to kill me turned out to be more expensive than my whole car. For drama, October 2014 doesn’t compare to December 1984.

Nine years later, after six years working as an editor for Whittle Communications, the unlikeliest journalistic enterprise in Knoxville history, I was associate editor for an ostensibly national publication aimed at doctors’ waiting rooms. It shouldn’t have worked, and didn’t. Five years after its splashy launch, advertised with full-page ads in the New York press, it was just over. At the time, my kids were 3 and 8. Though I found freelance and part-time work almost immediately, it was years before I found a job with family health benefits.

This time, my wife and I no longer have dependents. Both kids are college graduates with good jobs. The afternoon before we got the news about Metro Pulse, my tax accountant had reminded me, rather grimly, that for the first time in almost three decades we were no longer eligible for tax deductions.

I’m just saying that for me, the timing could have been worse.

Most of my colleagues have more diverse backgrounds in media than I do, and it’s safe to say they’re all handier with social media than I am. They’ll land on their feet.

Today I’m still a guy who writes words for public consumption, but for the moment I’m no longer a journalist, at least not any more than everybody else in our bloggy world. There’s no longer a reason for people to get nervous when I walked into a room. They’ll no longer look at me uncertainly and say, “This is off the record, right?” Then again, I’ll also get fewer tickets to shows, fewer invitations to receptions, fewer tours of renovated buildings. I’ll adjust.

There are a few things I won’t miss. After 19 years, there were some things I was getting weary of. The name is one. “Metro Pulse” sounds like something a fresh college grad came up with in the early ’90s, employing words trendy among alt weeklies back then, and it was exactly that. I once led a minor campaign to rename Metro Pulse, and failed. Some other staffers disliked it, too, but convinced me the brand had momentum with advertisers and readers alike, and we didn’t need to mess with that.

And by 2002 or so, some former colleagues will affirm, I thought the column called Secret History had run its course. I’d made my point, and wanted to move on to something else. But I kept writing it, just because I didn’t know where to stop, and could never think of the other thing I was going to do. Since I began it as an occasional freelance column in 1992, I’ve written about 1,000 of them. And I’m afraid there are still several thousand more in my to-do files. Maybe I’ll get to them somehow, if only here on this here website.

I can’t predict the future of print journalism. Learned people declare the Internet is killing it.

Much of that assumption’s based on the premise that what we want, need, and are able to sustain and afford in the last dozen years or so is what we’ll want and need and be able to sustain and afford forever. Computer technology is amazing, but it’s also the most expensive and complicated means of mass communication in human history. The computer I’m working on cost hundreds of dollars, and it’s nine years old, and it’s no longer working perfectly. Nine years isn’t old for a lawn mower or a refrigerator or a radio, but for a computer, it’s beyond elderly, officially too old even to donate to the homeless.

And most unsettling to me, the Internet’s promise of unlimited storage is already proving fallible. If I want to find a newspaper column that Bert Vincent or Carson Brewer wrote in 1955, it’s as easy as a quick trip to the library; they’ll have it in both paper clipping form and on microfilm. But try to find a column I wrote in, say, 2007, using the Internet, and you may find it somewhere, but then again, you may not. It’s a matter of luck. Some things I wrote 15 years ago are still getting batted around. A couple of old pieces I still get responses to, from people on other continents who seem to assume I wrote them last week, and that’s amazing. More typically, even if these articles got linked around a lot at the time, they vanish, and all you get from Google is an “Error” message. Or, perhaps worse, they get changed and garbled somehow. I don’t know how it happens, but things just e-rot somehow. The pictures vanish, or change to other pictures of something else. Last week I looked for one piece I was especially proud of, from 2006. I found that several links to it had shut down. When I found one copy, it was missing a few things. And it had another reporter’s name on it.

I’m proud to say the McClung Collection keeps a cardboard file with my name on it, and paper clippings within, and they’ll be legible in 100 years.

It’s a brave new world. Maybe we’ll adjust our expectations of the past to suit the Internet’s busy decrepitude. Maybe in the future the past will no longer exist.

I digress.

But I suspect that much of the assumption that the Internet is killing print journalism is connected to the post-hoc-ergo-propter-hoc fallacy. But the fact is, newspapers have been failing for 300 years. But somehow all newspapers that have closed since about 2000 have closed because of the Internet. It’s the new excuse, and a handy one designed not to hurt feelings. You don’t have to say you weren’t imaginative enough, or smart enough, or that you didn’t have your heart in it, or that you didn’t work hard enough. “It’s because of the Internet.” Of course.

Some of the most notable newspapers in Knoxville history did not outlast Metro Pulse by much. The first newspaper in Tennessee history was the Knoxville Gazette, which notably opened publication in 1791, when Knoxville hardly existed, with the serial publication of a Thomas Paine’s controversial book-length essay, The Rights of Man. It was a heroic thing, on the dangerous frontier, to bring such interesting concepts to practical-minded people. The Gazette barely survived its founder’s sudden death, and lasted a total of 27 years. The most famous newspaper in local history, Brownlow’s Knoxville Whig, the searing Unionist paper which caused its editor to be burned in effigy as far away as Texas, lasted only 20 years. Metro Pulse lasted 23 years. It’s a pretty good run, historically.

If alternative dailies are dying because of the Internet, as some claim, Metro Pulse is a particularly contrary example. Metro Pulse lost money for most of its 23 years. Some years in the ’90s were especially dire.

But last year, the year before, and the year before, our old paper was doing better than ever, breaking even, even making a modest profit now and then. It took painful pay cuts and long hours to make that happen, but we finally arrived at that place, and having arrived there, felt confident about the future.

Individual owners and corporate owners have different standards for what makes a business viable. They have different motivations. Individuals have more fun with their investments.

You can compare a free weekly to a yacht. Individuals sometimes have yachts, just for the enjoyment of having a yacht. Yachts are sometimes beautiful and fast and worth the trouble.

You enjoy a yacht, you go places in a yacht. Maybe you’re proud of it, you tell people at the opera or the golf course that you own a yacht, and it starts a conversation. Maybe you have a party in a yacht and invite all your friends. But you don’t necessarily expect to make money on a yacht. It’s good to minimize your losses, but making a profit on a yacht is an extraordinary thing. The same is true for an Airedale or a swimming pool or a BMW. The same is true for an old theater or a high school or a city’s government. Most of these things don’t turn big profits. That doesn’t suggest those things are worthless, or unsustainable, or dying.

Some magazines are run like yachts. The New Yorker is one of America’s oldest and most respected magazines, has always been owned by individuals, not corporations. It does not make a profit, as a regular thing, and didn’t make a profit even in its long-ago days before the Internet, when James Thurber and E.B. White worked there. It’s a weekly publication that does not predictably make any money at all. But it’s 90 years old, and nobody’s counting off their final days. That’s just because certain individuals like to own the New Yorker, maybe because they like to read the New Yorker.

Maybe people wouldn’t mine coal or manufacture chicken parts unless it was an industry that predictably made big profits. For those businesses, profit is the main thing. Maybe journalism is different. Maybe it’s more like a school or a museum, making income, perhaps sometimes with a surplus, but with occasional losses covered by philanthropists.

Earlier this month, the University of Tennessee’s business school got a single gift, from a single local individual, in an amount that would sustain the staff, printing, and distribution of a free weekly newspaper–like Metro Pulse–for more than a century. (I don’t expect that to happen, especially not with that individual.)

I’m more certain about another thing. I’ve watched this newspapering matter pretty closely, from within and without, for the last couple of decades. There’s a good market and, more urgently, a need in my hometown for something like Metro Pulse. By any other name.